Tournants et bifurcations, acteurs de la vasoocclusion drépanocytaire?

La drépanocytose affecte plus de 50 millions de personnes dans le monde et se caractérise par des crises douloureuses de vasoocclusion dont la localisation exacte dans la microcirculation des tissus profonds reste inconnue. Une étude microfluidique et numérique réalisée par trois équipes multidisciplinaires de Montpellier, démontre pour la première fois que des cellules sanguines se déposent préférentiellement aux tournants à fortes courbures, et notamment aux bifurcations, caractéristiques de la microcirculation. Ces travaux qui mettent en évidence le rôle majeur que pourrait jouer la géométrie de l’écoulement dans l’avènement des crises occlusives, sont publiés dans la revue Biophysical Journal.

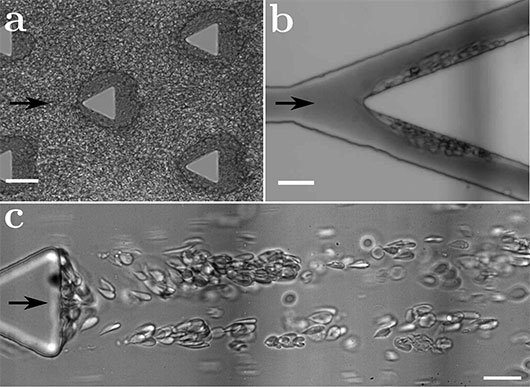

La drépanocytose est une hémoglobinopathie héréditaire qui affecte plus de 50 millions de personnes dans le monde. Elle se caractérise par des crises douloureuses vasoocclusives dans la microcirculation des tissus profonds. Les symptômes proviennent d'une mutation singulière produisant une hémoglobine anormale nommée HbS dans les globules rouges. Lorsqu'elles sont désoxygénées, ces molécules d'HbS polymérisent en fibrilles traversant le globule rouge de part en part, en le déformant au repos sous une forme tristement célèbre de faucille, donnant son nom à la maladie. La perte de déformabilité résultante serait responsable d'évènements vasoocclusifs récurrents et délétères. Au cours des trois dernières décennies, la physiopathologie des crises vasoocclusives s'est avérée plus complexe que l'explication logique, mais trop simpliste, d'un colmatage des vaisseaux sanguins par encombrement de globules rouges rigidifiés après relargage de leur cargo d'oxygène et polymérisation de leur hémoglobine. Notamment, des scénarios complémentaires basés sur des variations permanentes des propriétés de la membrane de ces globules, telle que leur adhérence accrue entre eux et aux parois vasculaires, ont été proposés. Des cascades adhésives de globules rouges pourraient produire de la vasoocclusion par accumulation catastrophique dans les veinules postcapillaires, même si aucune description détaillée de la dynamique d'occlusion n'est encore disponible à ce jour. La déposition et l'agrégation des globules rouges seraient en fait favorisées par un état inflammatoire chronique chez les patients souffrant de la drépanocytose, état résultant du stress oxydatif associé à l'hémolyse plus fréquente de leurs globules rouges plus fragiles. Jusqu'à présent, aucun des scénarios proposés n'a examiné le rôle éventuel joué par la géométrie de l'écoulement sur la déposition et la question de l'emplacement exact des événements occlusifs à l'échelle de la microcirculation reste ouverte. Des chercheurs du Laboratoire Charles Coulomb, de l’Institut de Mathématiques, de l’Institut de Biochimie Structurale et de Modélisation et du Laboratoire d’Hématologie de la Faculté de médecine de Montpellier, révèlent pour la première fois, grâce à l’utilisation de puces microfluidiques, que des agrégats cellulaires se forment par déposition successive de globules rouges drépanocytaires, préférentiellement autour de coins prononcés de piliers triangulaires ou de bifurcations. Cette accumulation localisée conduit à des agrégats géants flottant au milieu du canal. Puisque la microcirculation est formée de vaisseaux présentant généralement de fortes courbures, des formes ondulées, et un grand taux de bifurcations avec des longueurs de segments courts entre les bifurcations du réseau, les chercheurs proposent que ces caractéristiques géométriques pourraient jouer un rôle majeur dans le développement d'évènements vasoocclusifs in vivo.

figure : Formation d’agrégats dans une puce microfluidique mimant la microcirculation. (a) Formation d’agrégats de globules rouges drépanocytaires au niveau de coins prononcés. La flèche indique le sens de l’écoulement et la barre d’échelle représente 50 µm. (b) Agrégats de globules drépanocytaires au niveau d’une bifurcation. La barre d’échelle représente 20 µm. (c) En présence de plasma autologue, les agrégats adoptent une morphologie différente de celle présentée en (a) et forment de longues chaînes qui flottent au milieu du canal. La barre d’échelle représente 20 µm. © Manouk Abkarian

En savoir plus: Microfluidic study of enhanced deposition of sickle cells at acute corners and its possible role in vaso-occlusion. E. Loiseau, G. Massiera, S. Mendez, P. Aguilar Martinez and M. Abkarian. Biophysical Journal, Vol. 108, Issue 11, p2623–2632. dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2015.04.018 Contact chercheur Manouk Abkarian Centre de Biochimie Structurale CNRS UMR 5048, Inserm U1054, Université de Montpellier 29 rue de Navacelles 34090 Montpellier Cedex Tel :04 67 41 77 13